When I was a kid, there was an ad that ran in virtually every comic book for a “Polaris Nuclear Sub” that was “Big Enough for 2 Kids” and “Sturdily constructed of 200 ib. test fibreboard.” Of course I begged my parents to buy it for me, but my dad pointed out that “fibreboard” was just cardboard and we had plenty of that. So together we built a submarine our of cardboard boxes, and it was better than anything we could have mail-ordered for $6.98 plus 75¢ for shipping and handling.

Fast-forward to 2024, when I learned of the existence of a Live Action Role Playing event called Feindfahrt (), an anti-war LARP held in the submarine set originally built for Das Boot (1981), which also happens to be one of my favorite films ever. Of course I had to sign up for it, and as I write this I’m on a plane home from Munich where I just finished playing it.

Massive SPOILERS for the game follow. Proceed at your own risk.

The fictional premise of Feindfahrt is that after the capture of the German submarine U-505 (this really happened, and the sub is currently on display at the Museum of Science and Industry in Chicago), the Allies decided to staff the captured sub with a mix of US and UK sailors and send it deep into enemy territory on a secret mission. The intent of the game was to give players a sense of how oppressive and cruel the life of submariners during WWII was, with a good dose of interpersonal drama as well. It wasn’t intended to be a realistic submarine simulation or a strategic military game, but a game of communication and psychology in a tense and claustrophobic setting. There were 35 players of all genders (playing characters of all genders, in one of several departures from historical accuracy) drawn from countries including Germany, France, the Netherlands, Sweden, Norway, Finland, and the UK. I was the only person who came all the way from the USA for the game, though several other players were Americans who lived in Europe.

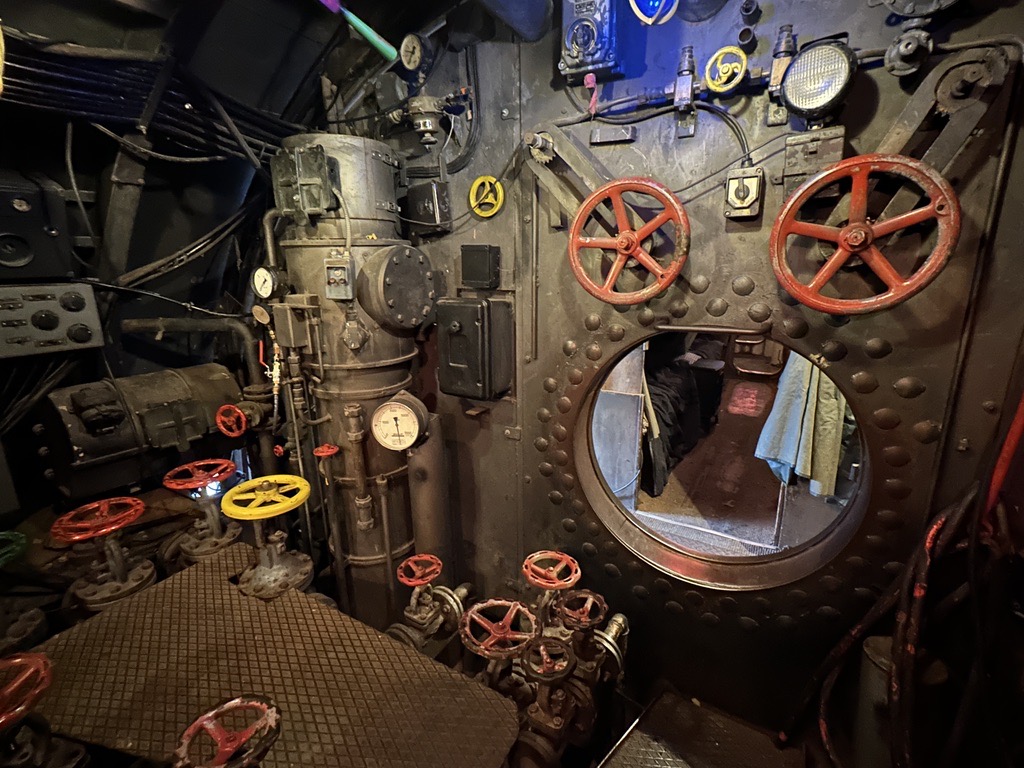

The Das Boot set is a life-sized recreation of the full interior of a Type VII-C German U-boat, 60 meters long and about 6 meters wide. During filming the set was mounted on a hydraulic platform that could tilt through 45 degrees in 5 seconds in both the pitch (fore-and-aft) and roll (side-to-side) dimensions to create dramatic scenes of diving, rolling in high seas, and being shaken by depth charges. Today the set sits on solid ground under a tent at the Bavaria Filmstadt studio. Which, given that the high temperatures in Munich this week were 39-45 degrees Fahrenheit, meant that it was as cold as the North Atlantic in there. However, we were forewarned about this, so I packed two sets of long undies, lots of wool socks, and a heavy sweater and I was reasonably comfortable the whole time.

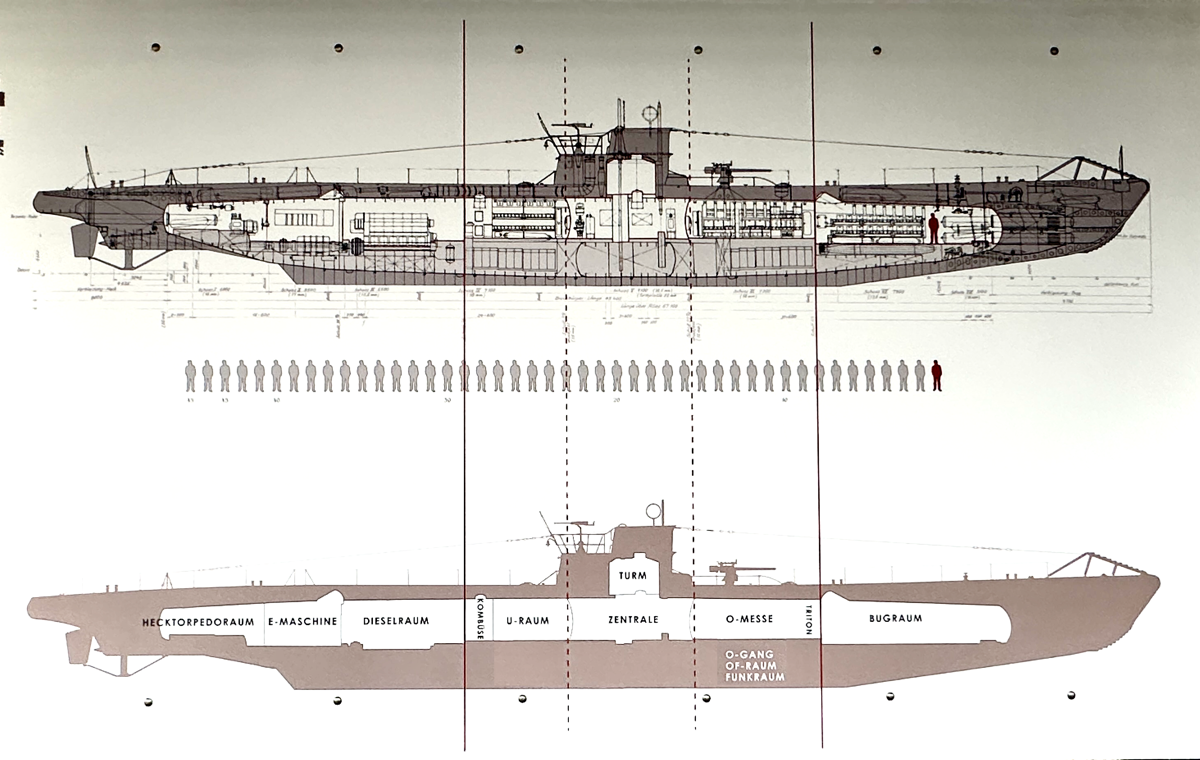

As you can see from the above diagram, the boat was equipped with a Heckin’ Torpedo Room, an E-Machine, and a Bug Room. (Not really.) From left to right they were Aft Torpedo Room; Electric Engine Room; Diesel Engine Room; Galley; Non-Commissioned Officers’ Quarters; Control Room and Conning Tower; Officers’ Quarters, Radio Room, and Sonar/Hydrophone Room, Head, and Forward Torpedo Room. When I say “quarters” I mean “tightly packed bunks with a narrow passageway in between;” the enlisted men slept in shifts in hammocks slung between the torpedoes. Note the size of the little red person at the forward end of the top diagram; we’re talking cramped here.

We spent 12-13 hours per day in the sub, but we didn’t sleep there. The set did not actually have enough bunks to sleep 35 players even in shifts, and also it was terribly cold and the head wasn’t functional. So we all had to find our own accommodations in a nearby(ish) hotel (I chose the Bio-Hotel Alter Wirt, https://www.alterwirt.de, five stars would stay again) and commute to the submarine each day. We could easily leave the set whenever we wanted to, for bathroom breaks or just to decompress, and took our meals in a heated building nearby. I personally never felt particularly claustrophobic.

The set was not and had never been a real submarine. For one thing, the interior walls were painted black to create a claustrophobic feeling, whereas in a real sub they are painted in light colors for exactly the opposite effect. The controls and indicators were almost all nonfunctional and in many cases not technically accurate. Many parts that would have been metal in a real sub were made of wood or drywall, and were also over 40 years old, so we were repeatedly reminded to be careful not to break the sub. Despite these limitations the whole thing was incredibly detailed and immersive and I would definitely describe it as the Biggest, Best Toy EVAR. Also, the LARP organizers had repaired the diesel engine prop so that it moved realistically (after being broken for 18 years) and added some functional instruments such as depth gauges, battery meter, and speedometer; Arduino-powered interactive hydrophone and sonar; telephones for communication between the bridge, engine room, and torpedo room; and video screens so that people in other parts of the boat could see what was on the periscope. And there were speakers throughout to provide realistic sound effects such as rushing water, the hull creaking under strain, and depth charges exploding nearby.

In most European LARPs I’ve played there are a few non-player characters (NPCs) mixed in with the players to provide advice, guidance, and emotional support and keep the game from going off the rails. In this case, given the small cast of 35 players and confined play space, we had just one NPC, the Chief Engineer. But the organizers also did have cameras throughout the sub and were listening in on all phone conversations. This meant that sometimes we had to do things such as, for example, calling the bridge from the engine room to report that the speedometer was showing zero when the engines were running all ahead full, after which the speedometer would quickly correct itself. There was also a “red phone” (actually black) which we could use to contact the organizers directly. The organizers, in turn, could communicate to us in the form of radio transmissions from HQ, at least when we were surfaced.

Our characters were pre-written and assigned to us based on a fairly brief questionnaire about our preferences. The character descriptions were well-written and quite detailed, giving a full rundown of the character’s background, personality, motivations, and relationships with other characters. I played CPO Robert Johnson, the Chief of the engine room, a highly experienced and trustworthy engineer who was generally on good terms with everyone — though he could be stubborn and persnickety on technical matters. The one person on the boat he didn’t like was the Executive Officer, under whom Johnson had previously served on the submarine Seahorse. The Seahorse had sailed into a minefield in a storm, killing most of the crew, and Johnson blamed her captain (now U-505’s XO) for the disaster. However, other player characters who had also been there considered him a hero for saving anyone at all. Johnson also disliked the boat itself, as his father had been the engineer on a civilian ship that was torpedoed by a German U-boat early in the war, but saw it as his duty to keep this cold-blooded German war machine running smoothly for the sake of the mission and the crew.

Creative costuming is a big part of many LARPs, but in this case we were all in uniform, so all we had to provide was dark pants, dark waterproof shoes, and whatever long undies we wanted. US Navy sailors were issued khaki shirts, cardigans of various colors, and white sailor caps; Royal Navy sailors got dark blue cardigans and hats with ribbons; and officers got pea coats and big fancy officer hats. (Amusingly, I was Royal Navy, the only non-American in my watch; my watch mates were all American, but all played by non-Americans.) We also got embroidered name tags and drinking cups with our character names on them. I was rather alarmed that my name tag was bloodstained, and I was informed that my character in the previous run had lost an arm!

Having been handed our characters and issued our orders by headquarters, everything else in the game was improvised. It was up to each player to decide what to do and say minute by minute, and we each reacted to developing situations and other characters’ actions according to our characters. But we were given some guidance to keep the game moving and fun: to choose drama and action over passivity and inaction, and to treat each other as experts in our fields and accept any improvised technobabble as gospel. Thus, if a player said that the frammistat needed to be reflanged, then by God that frammistat did need reflanging. This created a potential problem when I wanted to send a junior ensign on a wild goose chase: I had to make sure that the other members of the crew, most of whom did not have English as a first language, understood that a request for a “left-handed monkey wrench” or “sixty feet of waterline” was NOT to be treated as gospel but as a nonexistent item, a deliberate prank.

The first half-day of the game was spent in orientation and workshops, as is typical for European LARPs. We spent time in groups getting to know the other members of our duty station (bridge, engine room, or radio/torpedo room), our watch (we were divided into two watches), our navy (US or UK; there was some tension between the two), and in some cases sailors we’d served with previously on the Seahorse or other vessels. We then got a tour of the set and some instruction in “how to U-boat.” In the afternoon we got into costume and into character for a shakedown cruise near Bermuda (where the sub had been taken after being captured). We took the sub and crew through their paces and uncovered some issues, notably in communication. (Bridge: “Engine room, take her down to 15 meters.” Engine room: “Not our department, you’ve got the controls for the ballast tanks and dive planes right there. We make ship go fast and slow, you make ship go up and down.”)

My Engine Room crew’s jobs were to run the diesel and electric engines as commanded; use the rudder control wheel to direct the sub’s heading, again as commanded; keep all mechanical systems running smoothly; and fix anything that went wrong. Given that most of the controls on the sub were nonfunctional props, this involved a lot of “stare meaningfully at a gauge while tweaking a knob” and “pretend something broke and pretend to fix it.” As the game went on, though, there was less making-up of problems and more problems appearing from sources external to our team, which made for more satisfying play. And everything is more fun when you work with other people, so I made sure to send people out to fix things in pairs.

We really did start to work together as a team and I felt a great camaraderie with my people. One superstition we decided on as a team was that it was bad luck to point at anyone or anything with one finger — you should instead use two or more fingers, a thumb, or your whole hand. (This is, apparently, a real superstition in the Swedish Navy). If you violated this rule you had to knock three times on the overhead to regain your luck. Like saying “Macbeth” in a theatre, this was our superstition but anyone around us could get dinged for running afoul of it.

Then we skipped forward in time a few months for a scene set at a drunken party in a Scottish coastal town right before launch. But the party was interrupted by an air raid siren, and we all staggered out into the street heading for the nearest shelter… and then the bombs started falling, with real explosions and fire all around. It was a spectacular and dramatic opening to the game! Once we arrived at the bomb shelter we flashed back three days to a meeting with an Admiral in which we were all requested to write a letter to our next of kin, to be delivered in case we did not come back. On that sobering note the first day of play ended.

Before the second day of play began we were offered a chance to “calibrate” with other players about what we might want from them or offer to them. I said my character sheet indicated I was not bearing up well under the strain, and that I intended to have some kind of break late in day 2 or early in day 3, though I couldn’t say when or what kind of break it would be.

The second day of the game opened with us already out at sea, where we received our orders: join a German U-boat wolf pack and accompany them back to their base, where we would use our torpedoes to destroy an important fuel depot which was protected from aerial attack. To many of us this seemed like a likely suicide mission, and my pointed questions about how exactly we were going to get away from the exploding sub pen were waved off.

We successfully located the wolf pack and made contact with them using stolen German codes, but then the pack moved to attack a civilan convoy. After one of the German subs torpedoed an Allied ship, we fired a second torpedo into it to demonstrate our bona fides. This was, for many of us, a morally indefensible choice. The captain pointed out that the ship was already sinking when we torpedoed it, but others protested that we’d almost certainly killed people who might otherwise have made it to lifeboats. As we submerged and ran from the scene, I collapsed in tears, saying “I feel like I just killed my own father!” As my crew helped me move through the bridge to my bunk one of the bridge officers asked if I was okay. “I’m a fucking war criminal!” I replied. Eventually, with the help of my crewmates, I calmed myself down, but I wasn’t the only one who had severe qualms about our actions.

As we made our way through the minefield surrounding the base I was called to the bridge to offer my technical expertise on getting the sub out of the harbor after launching our torpedoes. With the help of my second in command, my best friend on the boat, I advised that we would need at least two sub lengths ahead of us, or one length behind us, clear of any obstacles in order to reverse course. I was ordered to work with the sonar operator to make that decision — as soon as the fuel depot blew he would send out a ping and I would have five seconds to choose a course for our escape based on what came back. The ping showed clear both fore and aft, so I recommended a forward path as the quicker of the two options. That got us out of the immediate vicinity, but as we were beginning to run away another sub fired a torpedo at us. Thinking quickly, the XO — the man I believed had killed the Seahorse — ordered us to fire one of our own torpedoes at it, with the fuse set to just five seconds. The two torpedoes detonated right in front of us, damaging our bow but allowing us to slip away in the chaos. Thinking us destroyed, the Germans did not pursue and we made it through the minefield and into the open ocean without further incident. Thus ended the second day.

Calibrating at the beginning of day 3 I said that I’d been happy to be the supportive officer, directing my crew and doing my best to make sure everyone got as much game play as they desired, but I would like to do more fixing of problems as an individual contributor. (Cue ominous foreshadowy music.)

The third day’s play opened with us steaming away from our successful raid on the fuel depot, when we were ordered to pick up a “high value target” off the coast of The Netherlands. On the way there we had a strange noise on the hydrophone which my second-in-command speculated might be something caught in our propellors. I suggested reversing the engines briefly to clear the possible problem, and damn if it didn’t work! Later on there was a distressing hiss coming from something on the bridge; I tracked it to an air leak and patched it with period-appropriate chewing gum.

Evading both German and British ships as we approached the German-occupied Netherlands, we rendezvoused with a German speedboat, which handed us a defecting German scientist who specialized in the behavior of gases under pressure. But as we headed back out to sea the speedboat was intercepted and sunk by a British destroyer. The destroyer then pursued us, pounding us with depth charges. (I don’t think there was ever an in-game reason given why we didn’t just surface and surrender.) We took heavy damage and began to sink uncontrollably. Water shot from the walls (thankfully it was warm water) and I and the other engineers worked feverishly to patch the leaks. Once we got that problem solved the air compressor, which was needed to start the engine as well as to blow the ballast tanks, began to hiss and spew high-pressure air and we had to fix that. But though we stopped the air leak, the compressor itself was shot. Eventually we settled on the bottom, well below our maximum rated depth, with the hull creaking alarmingly and batteries and air running out fast.

With no air compressor to blow the ballast tanks or start the engines, and no forward motion to make use of the dive planes, we were well and truly stuck on the bottom. I had the idea of attempting to start the diesel engines (usually a Very Bad Idea while submerged) in hopes of pushing compressed air from the engine to the ballast tanks, but that didn’t work. I tried asking the German scientist who specialized in pressurized gases, but she didn’t have any ideas we hadn’t already tried. We did have hand bilge pumps but pumping them with all our might didn’t help. Finally the NPC Chief Engineer presented an unexpected solution involving sending volunteers diving into the pitch-black bilge (actually they went outside the sub, with hats pulled down over their eyes, and could only work as long as they could hold their breath) to find some strangely-shaped knobs, fit them to the corresponding attachments, and thus open the necessary valves to permit the bilge pumps to pump water out of the ballast tanks. This felt to me like an arbitrary escape-room-ish puzzle, and it left most of the players just shivering in the dark with nothing to do but hope it would work, but we did manage to find all the necessary valves before running out of volunteers and it did indeed work, allowing us to pull ourselves off the bottom and limp to the surface.

So we cheated death… barely. But as we were triumphantly steaming home we received a third assignment: to torpedo a ship carrying a German super-weapon. Upon receiving this order I lost my temper and repeatedly insisted that the sub was too badly damaged to survive anything resembling combat. This turned into a heated exchange with the Chief Engineer. He and I stood practically nose-to-nose, me with my arms crossed on my chest, saying with cold fury “In my professional opinion, SIR, any attempt to engage the enemy will inevitably result in the loss of this vessel and all hands, SIR.” He ordered me to conduct a full inspection and repair all problems found. “I can tell you without doing an inspection that this vessel is beyond our capabilities to repair, SIR. We need to return to port and careen her, SIR.” He repeated that this was an order. “Then I am insubordinate, SIR.”

He relieved me of command and had me hauled to the brig. But we didn’t have a brig, so he said to put me in the head. But there was only one head and we couldn’t afford to be without it. Another officer, more sympathetic to me, offered to take me off my superior’s hands, and he was happy to be rid of me. By this point I realized that my choices had been reduced to: die handcuffed to my bunk, or do what I could to save my crewmates (and most likely die trying). I chose option 2. I told my new commanding officer that I’d do what I could, but it would take as long as it took and I would be honest in my assessment of the situation. He set me to work beginning with the forward torpedo tubes, which had been damaged by our own torpedo as we escaped from the fuel depot the previous day.

We broke for dinner at that point, and several players inquired anxiously as to whether I was okay. “My blood is fizzing,” I said, “but I’m having a blast.” In the LARP community we call this “type 2 fun,” meaning that “my character is miserable but I’m enjoying myself.”

After dinner I kept trying to fix what I could in the time remaining, but I was really pessimistic. Basically, as I’d thought, the ship was absolutely beat to shit. “If we fire even one torpedo,” I said, “I estimate the chance of it getting stuck in the tube and detonating right there is over 25%. And I don’t recommend taking the boat below 50 meters.” The XO gave a big angry speech about how our duty was to the Navy and to Britain, that we were to follow orders, that this was not a democracy, but that we would do as we were told, without question, in order to save democracy from the fascist threat. But I realized that my loyalty was, and always had been, not to the Navy or to Britain but to my fellow crew members, and that saving their lives was more important to me than duty or honor. I had sacrificed my reputation, my position, and finally my career in attempt to save them, and spending all those chips hadn’t worked. But I had one chip left — I could work as an individual to try to fix the ship — and so I resolved to spend that one as best I could.

I was continuing to try to fix the spavined engine when we intercepted the target and, somewhat to my surprise, did manage to successfully fire a torpedo and sink it. But the target vessel was not alone — the area was swarming with German destroyers — and in fairly short order they began depth-charging the hell out of us. Explosions pounded our ears, I flung myself around the engine room like a member of the Star Trek bridge crew, the depth gauge fell and fell, and the lights went out. Then we heard the music indicating the end of play. Game over, man.

We all silently filed out of the sub and walked back to the air raid shelter, where we saw the same Admiral we’d seen before instructing a lieutenant to send the usual condolences to the families of those lost on the Allied ship we’d helped to sink, and also those lost on the U-505. Then we heard a voice reading a letter. It was, I soon realized, one of the letters we’d written to our next of kin in that same room at the beginning of the game. More and more voices joined in then, all the letters overlapping in a Greek chorus of farewell. I certainly recognized my own words in there, and I imagine most everyone else did as well. And then the game was over. Roll credits.

There was an afterparty, but between jet lag and emotional exhaustion I faded out after less than an hour. As I walked past the sub on my way back to my hotel, I noticed that the sound system had not been turned off and there were still gurgling noises coming from the tent. Bubbles coming up from the bottom, I guess.

That ending felt so right and seemed so inevitable that I figured it had been on rails, but afterwards we learned that runs 1 and 2 of the game (we were run 4) had made it home alive, so our fate really was open, at least to some extent. I can’t point to any specific decision that sealed our doom or could have saved us, but I think that out-of-game timing was a big part of it. We succeeded in our first two missions quite quickly so there wound up being time for a third at the end, which is the one that killed us. If we had finished our second mission closer to the end of the day Saturday, the game might have ended there with us still afloat or even home safe.

The pivotal moment of the game for me was when my character stood up on his hind legs and defied authority, even though it didn’t change the outcome (or perhaps made it worse, as he might have succeeded in repairing the ship if he hadn’t wasted time in rebellion — though I strongly doubt it). It reminds me of my favorite scene in the Westworld game, where I resigned from my job and threw in my lot with the robots — though in that case I did manage to save some lives, including my own. Perhaps I’m just a rebel at heart? But I can tell you that, unlike my breakdown on the previous day or my Westworld resignation, I did not plan that scene, or even anticipate that it would happen. It just emerged naturally from my character in the moment, especially from his experiences on the Seahorse (it said in my character sheet “He has sworn never to blindly trust an officer again when it comes to life and death”).

I don’t regret my actions, and indeed my conscience is at peace knowing that I did everything I could to save my crewmates. But in retrospect I’ve come to the conclusion that my character was actually in the wrong. In the end we achieved our goal — we achieved a major strategic victory — albeit at the cost of our lives and the ship, which is most likely the outcome the Admiralty expected when they gave the order. My attempt to disobey orders salved my conscience in the moment but in the larger context of the war was counterproductive and morally wrong.

On the other hand, if you take a bigger step backwards, was the war itself morally justified? But better people than I have been arguing this point for centuries, so I know I’m not going to be able to answer it. But considering these questions from the perspective of a realistic, immersive experience is, I think, the main point of this LARP.

Feindfahrt cost me a lot more than $6.98 plus 75¢ for shipping and handling. But in the end, the fun you make yourself is always the best.

Recent Comments