About the Story

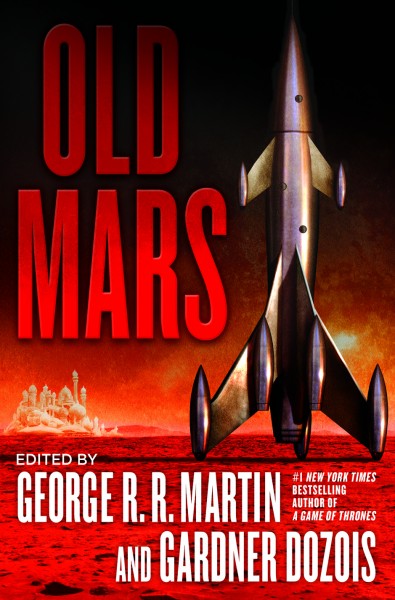

When I was fortunate enough to have an opportunity to submit to a new anthology edited by Gardner Dozois and George R. R. Martin about Mars — not the real post-Mariner Mars, but the one we all loved as kids, with the canals and the dead cities and the various flavors of Martian — I was tremendously excited and also a bit terrified. The editors alone, never mind the other authors who would be participating in the project, were among my science fiction heroes, and the topic was near and dear to my heart.

Fortunately, I had a unique idea to use for the project. I was working on a novel which takes place during the English Regency in an alternate universe in which the solar system is full of air and airship travel to the planets — which are inhabited, of course — is an accepted part of the world. One of the comments I received on an early draft of the novel opening was “how did they reach Mars in the first place?”

This story, describing Captain Kidd’s (yes, that Captain Kidd) journey to Mars in the year 1701, is the answer to that question.

Reviews

“This is indeed high adventure, a cracking good sailing yarn with skiffy values. I love the imaginative audacity of the premise. The author’s version of Mars is also remarkable. Highly entertaining. RECOMMENDED.”

—Lois Tilton, Locus Online

“The stories are without exception engaging and full of the old sense-of-wonder. It’s hard to pick standouts in this crowd, but be sure not to miss David D. Levine’s ‘The Wreck of the Mars Adventure,’ a tale of Captain Kidd’s 17th century expedition to Mars….”

—Don Sakers, Analog

“There is a steampunkish cast to some of the better stories. For example, David D. Levine’s “The Wreck of the Mars Adventure” features Captain Kidd recruited by the King to sail a ship to Mars — I have to admit to being something of a sucker for space sailing stories. The concept is pretty much the story here, but it’s very well done.”

—Rich Horton, Locus

Excerpt

Kidd stood at the rope which on any ordinary ship would be the taffrail, his stomach troubled.

All of his seafaring instincts told him his ship was completely becalmed. Floating beneath her balloons, she drifted along with the wind, so no breath of breeze freshened the deck. Sexton with his instruments assured Kidd that they were making good progress, but still he worried.

An unimaginable distance below, the whole great globe of the Earth lay spread out to his sight: a shiny ball of glass, swirled in blue and white, suspended in the blue of the sky. He could span the width of the world with two hands held out at arm’s length, thumb to thumb and fingers spread.

The drop was now so great that the view had passed from terrifying to interesting.

Sexton stood nearby, peering upward through his telescope, and Kidd moved closer to him. “Dr. Sexton,” he said, speaking low so that none of the other quarterdeck crew might hear, “I must confess myself uneasy. I’ve sailed through storms, battled pirates, and faced death by hanging, but this is the first time in my whole career I’ve felt such a tremulous sensation in my gut. My head is light as well, and my feet unsteady, and furthermore the quartermaster has told me he feels the same. Could this be some disease of the upper atmosphere?”

Sexton snapped the telescope closed. “‘Tis nothing more than the reduction of gravitational attraction.”

With all his learning, Sexton sometimes lapsed into Latin without realizing he had done so. “What is the treatment?” Kidd asked. “Bleeding? An emetic?”

At that Sexton laughed. “Fear not. It is no disease, but a natural consequence of our distance from the Earth. This phenomenon was predicted by Newton and confirmed by Halley on his first attempt to reach the Moon. As we travel further from the mother sphere, the attraction of her gravity — in layman’s terms, our weight — will grow less and less. Already we weigh only three-quarters as much as we would at home.” He bounced on his toes, and Kidd noticed the man’s wig bounding gently atop his head.

Kidd too bounced on his toes, and was astonished to find the small effort propelled him several inches into the air.

“Before the day is out,” Sexton continued, “we will pass out of the Earth’s demesne and into the interplanetary atmosphere. There we will exist in a state of free descent, and will feel ourselves to have no weight at all. That is the point at which we will be able to retire the balloons and continue with sails alone.”

No matter how many times Sexton had explained this phenomenon, Kidd had never quite been able to comprehend it. But now, with his thirteen stone pressing so lightly against his feet, he felt he was beginning to understand. Again he hopped lightly into the air, feeling himself float giddily for a moment before his boots struck the deck. “I see,” he said.

While Kidd had been bouncing, Sexton had resumed his telescopic observations. “Of course,” he said, peering upward through the instrument, “we must first traverse the boundary between the planetary atmosphere, which rotates along with the Earth, and the interplanetary atmosphere, which orbits the Sun.” He collapsed the telescope. “There may be a bit of turbulence…”

Honors

Listed on the Locus Recommended Reading List.

Honorable Mention in Gardner Dozois’s Year’s Best Science Fiction.

Publications

-

- Old Mars, anthology, October 2013

- edited by Gardner Dozois and George R. R. Martin

- Bantam

-

- StarShipSofa, podcast, October 2015

- edited by Tony C. Smith

- StarShipSofa